Rashidun Caliphate

|

|

This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. (February 2015) |

| Rashidun Caliphate | |||||

| الخلافة الراشدة | |||||

| Caliphate | |||||

|

|||||

|

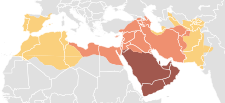

The Rashidun Empire reached its greatest extent under Caliph Uthman, in 654.

|

|||||

| Capital | Medina (632–656) Kufa (656–661) |

||||

| Languages | Arabic, Aramaic/Syriac, Armenian, Berber, Coptic, Georgian, Greek, Hebrew, Turkish, Middle Persian, Kurdish | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

| Government | Caliphate | ||||

| Amir al-Mu'minin¹ | |||||

| - | 632–634 | Abu Bakr | |||

| - | 634–644 | Umar | |||

| - | 644–656 | Uthman | |||

| - | 656–661 | Ali | |||

| History | |||||

| - | Established | 8 June 632 | |||

| - | First Fitna (internal conflict) ends | 28 July 661 | |||

| Area | 8,400,000 km² (3,243,258 sq mi) | ||||

| Population | |||||

| - | est. | 21,400,000 | |||

| Density | 2.5 /km² (6.6 /sq mi) | ||||

| Currency | Dinar, Dirham | ||||

| Today part of | |||||

| Amir al-Mu'minin (أمير المؤمنين), Caliph (خليفة) | |||||

| Warning: Value not specified for "common_name" | |||||

| Caliphate خِلافة |

|---|

|

| Islam portal |

| Historical Arab states and dynasties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mashriq dynasties

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Maghrib dynasties

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Rashidun Caliphate (Arabic: الخلافة الراشدة al-Khilāfah ar-Rāshidah, c. 632–661) is the collective term comprising the first four caliphs—the "Rightly Guided" or Rashidun caliphs (Arabic: الخلفاء الراشدون al-Khulafā’ ar-Rāshidūn)—in Islamic history and was founded after Muhammad's death in 632 (year 11 AH in the Islamic calendar). At its height, the Caliphate controlled a vast empire from the Arabian Peninsula and the Levant, to the Caucasus in the north, North Africa from Egypt to present-day Tunisia in the west, and the Iranian plateau to Central Asia in the east. It was the largest empire in history by land area up until that point.

OriginEdit

After Muhammad's death in 632, the Medinan Ansar debated which of them should succeed him in running the affairs of the Muslims while Muhammad's household was busy with his burial. Umar and Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah pledged their loyalty to Abu Bakr, with the Ansar and the Banu Quraysh soon following suit. Abu Bakr thus became the first Khalīfatu Rasūli l-Lāh "successor of the Messenger of God", or caliph, and embarked on campaigns to propagate Islam. First he would have to subdue the Arabian tribes which had gone back on their oaths of allegiance to Islam and the Islamic community. As a caliph, Abu Bakr was not a monarch and never claimed such a title; nor did any of his three successors. Rather, their election and leadership were based upon merit.[1][2][3][4]

Notably, according to Sunnis, all four Rashidun Caliphs were connected to Muhammad through marriage, were early converts to Islam,[5] were among ten who were explicitly promised paradise, were his closest companions by association and support, and were often highly praised by Muhammad and delegated roles of leadership within the nascent Muslim community.

According to Sunni Muslims, the term Rashidun Caliphate is derived from a famous[6] hadith of Muhammad, where he foretold that the caliphate after him would last for 30 years[7] (the length of the Rashidun Caliphate) and would then be followed by kingship.[8][9] Furthermore, according to other hadiths in Sunan Abu Dawood and Musnad Ahmad ibn Hanbal, towards the end times, the Rightly Guided Caliphate will be restored once again.[10]

HistoryEdit

Succession of Abu BakrEdit

Abu Bakr was the oldest companion of Muhammad. When Muhammad died, Abu Bakr and Umar, his two companions, were in the Saqifah meeting to select his successor while the family of Muhammad was busy with his funeral. Controversy among the Muslims emerged about whom to name as Caliph. There was disagreement between the Meccan followers of Muhammad who had emigrated with him in 622 (the Muhajirun "Emigrants") and the Medinans who had become followers (Ansar "Helpers"). The Ansar, considering themselves being the hosts and loyal companions of Muhammad, nominated Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah as their candidate for the Caliphate.[11] In the end, however, Muhammad's closest friend, Abu Bakr, was named the khalifa (caliph) or "Successor" of Muhammad.[12] A new religion and a new circumstance had formed a new, untried political formation: the caliphate. Troubles emerged soon after Abu Bakr's succession, threatening the unity and stability of the new community and state.[citation needed]

After Muhammad's death, apostasy spread to every tribe in the Arabian Peninsula with the exception of the people in Mecca and Medina, the Banu Thaqif in Ta'if and the Azd of Oman. In some cases, entire tribes apostatised. Others merely withheld zakat, the alms tax, without formally challenging Islam. Many tribal leaders made claims to prophethood; some made it during the lifetime of Muhammad. The first incident of apostasy was fought and concluded while Muhammad still lived; a false prophet Aswad Ansi arose and invaded South Arabia;[13] he was killed on 30 May 632 (6 Rabi' al-Awwal, 11 Hijri) by Governor Fērōz of Yemen, a Persian Muslim.[14] The news of his death reached Medina shortly after the death of Muhammad. The apostasy of al-Yamama was led by another false prophet, Musaylimah,[15] who arose before Muhammad's death; other centers of the rebels were in the Najd, Eastern Arabia (known then as al-Bahrayn) and South Arabia (known as al-Yaman and including the Mahra). Many tribes claimed that they had submitted to Muhammad and that with Muhammad's death, their allegiance was ended.[15] Caliph Abu Bakr insisted that they had not just submitted to a leader but joined a community or Ummah of which he was the new head.[15] The result of this situation was the Ridda wars.[15]

Abu Bakr planned his strategy accordingly. He divided the Muslim army into several corps. The strongest corps, and the primary force of the Muslims, was the corps of Khalid ibn al-Walid. This corps was used to fight the most powerful of the rebel forces. Other corps were given areas of secondary importance in which to bring the less dangerous apostate tribes to submission. Abu Bakr's plan was first to clear Najd and Western Arabia near Medina, then tackle Malik ibn Nuwayrah and his forces between the Najd and al-Bahrayn, and finally concentrate against the most dangerous enemy, Musaylimah and his allies in al-Yamama. After a series of successful campaigns Khalid ibn Walid defeated Musaylimah in the Battle of Yamama.[16] The Campaign on the Apostasy was fought and completed during the eleventh year of the Hijri. The year 12 Hijri dawned on 18 March 633 with the Arabian peninsula united under the caliph in Medina.[citation needed]

Once the rebellions had been put down, Abu Bakr began a war of conquest. Whether or not he intended a full-out imperial conquest is hard to say; he did, however, set in motion a historical trajectory that in just a few short decades would lead to one of the largest empires in history. Abu Bakr began with Iraq, the richest province of the Sasanian Empire.[17] He sent general Khalid ibn Walid to invade the Sassanid Empire in 633.[17] He thereafter also sent four armies to invade the Roman province of Syria,[18] but the decisive operation was only undertaken when Khalid, after completing the conquest of Iraq, was transferred to the Syrian front in 634.[19]

Succession of UmarEdit

| Umar Commander of the Faithful (Amir al-Mu'minin) |

|---|

|

|

Related articles

|

Despite the initial reservations of his advisers, Abu Bakr recognised military and political prowess in Umar and desired him to succeed as caliph. The decision was enshrined in his will, and on the death of Abu Bakr in 634, Umar was confirmed in office. The new caliph continued the war of conquests begun by his predecessor, pushing further into the Sassanid Persian Empire, north into Byzantine territory, and west into Egypt. It is an important fact to note that Umar never participated in any battle as a commander of a Muslim Army throughout his life. He even did not kill a single person himself in any battle but never gave up and continued expanding the Islamic state.[citation needed] These were regions of great wealth controlled by powerful states, but long internecine conflict between Byzantines and Sassanids had left both sides militarily exhausted, and the Islamic armies easily prevailed against them. By 640, they had brought all of Mesopotamia, Syria and Palestine under the control of the Rashidun Caliphate; Egypt was conquered by 642, and the entire Persian Empire by 643.

While the caliphate continued its rapid expansion, Umar laid the foundations of a political structure that could hold it together. He created the Diwan, a bureau for transacting government affairs. The military was brought directly under state control and into its pay. Crucially, in conquered lands, Umar did not require that non-Muslim populations convert to Islam, nor did he try to centralize government. Instead, he allowed subject populations to retain their religion, language and customs, and he left their government relatively untouched, imposing only a governor (amir) and a financial officer called an amil. These new posts were integral to the efficient network of taxation that financed the empire.

With the booty secured from conquest, Umar was able to support its faith in material ways: the companions of Muhammad were given pensions on which to live, allowing them to pursue religious studies and exercise spiritual leadership in their communities and beyond. Umar is also remembered for establishing the Islamic calendar; it is lunar like the Arabian calendar, but the origin is set in 622, the year of the Hijra when Muhammad emigrated to Medina.

Umar was killed in an assassination by the Persian slave Piruz Nahavandi during morning prayers in 644.

Election of UthmanEdit

| Uthman The Generous – (Al Ghani) |

|---|

|

Before Umar died, he appointed a committee of six men to decide on the next caliph, and charged them with choosing one of their own number. All of the men, like Umar, were from the tribe of Quraish.

The committee narrowed down the choices to two: Uthman and Ali. Ali was from the Banu Hashim clan (the same clan as Muhammad) of the Quraish tribe, and he was the cousin and son-in-law of Muhammad and had been a companion to the Prophet from the inception of his mission. Uthman was from the Umayyad clan of the Quraish.

Uthman reigned for twelve years as caliph, during the first half of his reign he enjoyed a position of the most popular caliph among all the Rashiduns, while in the later half of his reign he met increasing opposition. This opposition was led by the Egyptians and was concentrated around Ali, who would, albeit briefly, succeed Uthman as caliph.

Despite internal troubles, Uthman continued the wars of conquest started by Umar. The Rashidun army conquered North Africa from the Byzantines and even raided Spain, conquering the coastal areas of the Iberian peninsula, as well as the islands of Rhodes and Cyprus.[citation needed] Also coastal Sicily was raided in 652.[20] The Rashidun army fully conquered the Sassanid Empire, and its eastern frontiers extended up to the lower Indus River.

Uthman's greatest and most lasting achievement was the final compilation of the Qur'an. Under his authority diacritics were written with the Arabic letters so that non-native speakers of Arabic can easily read the Qur'an without difficulty.

Siege of UthmanEdit

After a protest turned into a siege, Uthman refused to initiate any military action, in order to avoid civil war between Muslims, and preferred negotiations.[citation needed] His polite attitude towards rebels emboldened them and they broke into Uthman's house and killed him while he was reading the Qur'an.[citation needed]

Crisis and fragmentationEdit

| Part of a series on |

| Ali |

|---|

|

|

Related articles

|

After the assassination of the third Caliph, Uthman ibn Affan, the Companions of Muhammad in Medina selected Ali to be the new Caliph who had been passed over for the leadership three times since the death of Muhammad. Soon thereafter, Ali dismissed several provincial governors, some of whom were relatives of Uthman, and replaced them with trusted aides such as Malik al-Ashtar and Salman the Persian. Ali then transferred his capital from Medina to Kufa, a Muslim garrison city in current-day Iraq.

Demands to take revenge for the assassination of Caliph Uthman rose among parts of the population, and a large army of rebels led by Zubayr, Talha and the widow of Muhammad, Ayesha, set out to fight the perpetrators. The army reached Basra and captured it, upon which 4000 suspected seditionists were put to death. Subsequently Ali turned towards Basra and the caliph's army met the army of Muslims who demanded revenge for the murder of Uthman. Though neither Ali nor the leaders of the opposing force, Talha and Zubayr, wanted to fight, a battle broke out at night between the two armies. It is said, according to Sunni Muslim traditions, that the rebels who were involved in the assassination of Uthman initiated combat, as they were afraid that as a result of negotiation between Ali and the opposing army, the killers of Uthman would be hunted down and killed. The battle thus fought was the first battle between Muslims and is known as the Battle of the Camel. The Caliphate under Ali emerged victorious and the dispute was settled. The eminent companions of Mohammad, Talha and Zubayr, were killed in the battle and Ali sent his son Hassan ibn Ali to escort Ayesha back to Medina.

After this episode of Islamic history, another cry for revenge for the blood of Uthman rose. This time it was by Mu'awiya, kinsman of Uthman and governor of the province of Syria. However, it is regarded more as an attempt by Mu'awiya to assume the caliphate, rather than to take revenge for Uthman's murder. Ali fought Mu'awiya's forces at the Battle of Siffin leading to a stalemate, and then lost a controversial arbitration that ended with arbiter 'Amr ibn al-'As pronouncing his support for Mu'awiya. After this Ali was forced to fight the rebellious Kharijites in the Battle of Nahrawan, a faction of his former supporters who, as a result of their dissatisfaction with the arbitration, opposed both Ali and Mu'awiya. Weakened by this internal rebellion and a lack of popular support in many provinces, Ali's forces lost control over most of the caliphate's territory to Mu'awiya while large sections of the empire such as Sicily, North Africa, the coastal areas of Spain and some forts in Anatolia were also lost to outside empires.

In 661 CE, Ali was assassinated by Ibn Muljam as part of a Kharijite plot to assassinate all the different Islamic leaders meaning to end the civil war, whereas the Kharijites failed to assassinate Mu'awiya and 'Amr ibn al-'As.

Ali's son Hasan ibn Ali, the grandson of Muhammad, briefly assumed the caliphate and came to an agreement with Mu'awiya to fix relations between the two groups of Muslims that were each loyal to one of the two men. Mu'awiya gained control of the Caliphate and founded the Umayyad Caliphate, marking the end of the Rashidun Caliphate.

Military expansionEdit

| Abu Bakr | 632 | 634 |

| Umar | 634 | 644 |

| Uthman | 644 | 656 |

| Ali | 656 | 661 |

The Rashidun Caliphate expanded gradually; within the span of 24 years of conquest a vast territory was conquered comprising Mesopotamia, the Levant, parts of Anatolia, and most of the Sassanid Empire.

Unlike the Sassanid Persians, the Byzantines after losing Syria, retreated back to Anatolia and as a result, also lost Egypt to the invading Rashidun army, although the civil wars among the Muslims halted the war of conquest for many years and this gave time for the Eastern Roman/Byzantine Empire to recover.

Conquest of the Persian empireEdit

The first Islamic invasion of the Sassanid Empire launched by Caliph Abu Bakr in 633 was a swift conquest in the time span of only four months led by general Khalid ibn Walid. Abu Bakr sent Khalid to conquer Mesopotamia after the Ridda wars. After entering Iraq with his army of 18,000, Khalid won decisive victories in four consecutive battles: the Battle of Chains, fought in April 633; the Battle of River, fought in the third week of April 633; the Battle of Walaja, fought in May 633 (where he successfully used a pincer movement), and the Battle of Ullais, fought in mid May of 633. In the last week of May 633, the capital city of Iraq fell to the Muslims after initial resistance in the Battle of Hira.

After resting his armies, Khalid moved in June 633 towards Al Anbar, which resisted and was defeated in the Battle of Al-Anbar, and eventually surrendered after a siege of a few weeks in July 633 . Khalid then moved towards the south, and conquered the city of Ein ul Tamr after the Battle of ein-ul-tamr in the last week of July 633. By now, almost the whole of Iraq was under Islamic control. Khalid received a call of help from northern Arabia at Daumat-ul-jandal, where another Muslim Arab general, Ayaz bin Ghanam, was trapped among the rebel tribes. Khalid went to Daumat-ul-jandal and defeated the rebels in the Battle of Daumat-ul-jandal in the last week of August 633 CE. Returning from Arabia, he received news of the assembling of a large Persian army. Within a few weeks, he decided to defeat them all separately in order to avoid the risk of defeat by a large unified Persian army. Four divisions of Persian and Christian Arab auxiliaries were present at Hanafiz, Zumiel, Sanni and Muzieh.

Khalid divided his army into three units, and decided to attack these auxiliaries one by one from three different sides at night, starting with the Battle of Muzieh, then the Battle of Sanni, and finally the Battle of Zumail. In November 633 CE, Khalid defeated the enemy armies in a series of three sided attacks at night. These devastating defeats ended Persian control over Iraq. In December 633 CE, Khalid reached the border city of Firaz, where he defeated the combined forces of the Sassanid Persians, Byzantines and Christian Arabs in the Battle of Firaz. This was the last battle in his conquest of Iraq.[22]

After the conquest of Iraq, Khalid left Mesopotamia to lead another campaign in Syria against the Byzantine Empire, after which Mithna ibn Haris took command in Mesopotamia. The Persians once again concentrated armies to regain the lost Mesopotamia, while Mithna ibn Haris withdrew from central Iraq to the region near the Arabian desert to delay war until reinforcement came from Medina. Umar sent reinforcements under the command of Abu Ubaidah Saqfi. With some initial success this army was finally defeated by the Sassanid army at the Battle of the Bridge in which Abu Ubaid was killed. The response was delayed until after a decisive Muslim victory against the Romans in the Levant at the Battle of Yarmuk in 636. Umar was then able to transfer forces to the east and resume the offensive against the Sassanids. Umar dispatched 36,000 men along with 7500 troops from the Syrian front, under the command of Sa`d ibn Abī Waqqās against the Persian army. The Battle of al-Qādisiyyah followed, with the Persians prevailing at first, but on the third day of fighting, the Muslims gained the upper hand. The legendary Persian general Rostam Farrokhzād was killed during the battle. According to some sources, the Persian losses were 20,000, and the Arabs lost 10,500 men.

Following this Battle, the Arab Muslim armies pushed forward toward the Persian capital of Ctesiphon (also called Madā'in in Arabic), which was quickly evacuated by Yazdgird after a brief siege. After seizing the city, they continued their drive eastwards, following Yazdgird and his remaining troops. Within a short span of time, the Arab armies defeated a major Sassanid counter-attack in the Battle of Jalūlā', as well as other engagements at Qasr-e Shirin, and Masabadhan. By the mid-7th Century, the Arabs controlled all of Mesopotamia, including the area that is now the Iranian province of Khuzestan. It is said that Caliph Umar did not wish to send his troops through the Zagros mountains and onto the Iranian plateau. One tradition has it that he wished for a "wall of fire" to keep the Arabs and Persians apart. Later commentators explain this as a common-sense precaution against over-extension of his forces. The Arabs had only recently conquered large territories that still had to be garrisoned and administered. The continued existence of the Persian government was however an incitement to revolt in the conquered territories and unlike the Byzantine army, the Sassanid army was continuously striving to regain their lost territories. Finally Umar decided to push his forces to further conquests, which eventually resulted in the wholesale conquest of the Sassanid Empire. Yazdegerd, the Sassanid king, made yet another effort to regroup and defeat the invaders. By 641 he had raised a new force, which made a stand at the Battle of Nihawānd, some forty miles south of Hamadan in modern Iran. The Rashidun army under the command of Umar's appointed general Nu'man ibn Muqarrin al-Muzani, attacked and again defeated the Persian forces. The Muslims proclaimed it the Victory of Victories (Fath alfotuh) as it marked the End of the Sassanids, shattering the last strongest Sassanid army.

Yazdegerd was unable to raise another army and became a hunted fugitive. In 642 Umar sent the army to conquer the whole of the Persian Empire. The whole of present-day Iran was conquered, followed by the conquest of Greater Khorasan (which included the modern Iranian Khorasan province and modern Afghanistan), Transoxania, and Balochistan, Makran, Azerbaijan, Dagestan (Russia), Armenia and Georgia, this regions were later also re-conquered during Caliph Uthman's reign with further expansion into the regions which were not conquered during Umar’s reign, hence the Rashidun Caliphate’s frontiers in the east extended to the lower river Indus and north to the Oxus River.

Wars against the Byzantine empireEdit

Conquest of Byzantine SyriaEdit

After Khalid captured Iraq and firmly took control of it, Abu Bakr sent armies to Syria on the Byzantine front. Four armies were sent under four different commanders; Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah (acting as their supreme commander), Amr ibn al-As, Yazid ibn Abu Sufyan and Shurhabil ibn Hasana. These armies were all assigned their objectives. However their advance was halted by a concentration of the Byzantine army at Ajnadayn. Abu Ubaidah then sent for reinforcements. Abu Bakr ordered Khalid, who by now was planning to attack Ctesiphon, to march from Iraq to Syria with half of his army. Khalid took half of his army and took an unconventional route to Syria. There were 2 major routes to Syria from Iraq, one passing through Mesopotamia and the other through Daumat ul-Jandal. Khalid took a route through the Syrian Desert, and after a perilous march of 5 days, appeared in north-western Syria.

The border forts of Sawa, Arak, Tadmur, Sukhnah, al-Qaryatayn and Hawarin were the first to fall to the invading Muslims. Khalid marched on to Bosra via the Damascus road. At Bosra, the Corps of Abu Ubaidah and Shurhabil joined Khalid, after which here as per orders of Caliph Abu Bakr, Khalid took the high command from Abu Ubaidah. Bosra was not ready for this surprise attack and siege, and thus surrendered after a brief siege in July 634, (see Battle of Bosra) this effectively ending the Ghassanid Dynasty.

From Bosra Khalid send orders to other corps commanders to join him at Ajnadayn, where according to early Muslim historians, a Byzantine army of 90,000 (modern sources state 9,000)[23] was concentrated to push back the Muslims. The Byzantine army was defeated decisively on 30 July 634 in the Battle of Ajnadayn. It was the first major pitched battle between the Muslim army and the Christian Byzantine army and cleared the way for the Muslims to capture central Syria. Damascus, the Byzantine stronghold, was conquered shortly after on 19 September 634. After the Muslim Conquest of Damascus, the Byzantine army was given a deadline of 3 days to flee as far as they could, with their families and treasure, or simply agree to stay in Damascus and pay tribute.

After the three day deadline was over, the Muslim cavalry under Khalid's command attacked the Roman army by catching up to them using an unknown shortcut at the battle of Maraj-al-Debaj.[citation needed]

On 22 August 634 Abu Bakr died, making Umar his successor. As Umar became caliph, he relieved Khalid of command of the Islamic armies and appointed Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah as the new commander. The conquest of Syria slowed down under him while Abu Ubaida relied heavily on the advices of Khalid, and kept him beside him as much as possible.[24]

The last large garrison of the Byzantine army was at Fahl, which was joined by survivors of Ajnadayn. With this threat at their rear the Muslim armies could not move further north nor south, thus Abu Ubaidah decided to deal with the situation, and had this garrison defeated and routed at the Battle of Fahl on 23 January 635. This battle proved to be the "Key to Palestine". After this battle Abu Ubaidah and Khalid marched north towards Emesa, Yazid was stationed in Damascus while Amr and Shurhabil marched south to capture Palestine.[24] While the Muslims were at Fahl, sensing the weak defense of Damascus, Emperor Heraclius sent an army to re-capture the city. This army however could not make it to Damascus and was intercepted by Abu Ubaidah and Khalid on their way to Emesa. The army was routed and destroyed in the battle of Maraj-al-Rome and the 2nd battle of Damascus. Emesa and the strategical town of Chalcis made peace with the Muslims for one year. This was, in fact, done to let Heraclius prepare for defences and raise new armies. The Muslims welcomed the peace and consolidated their control over the conquered territory. As soon as the Muslims received the news of reinforcements being sent to Emesa and Chalcis, they marched against Emesa, laid siege to it and eventually captured the city in March 636.[25]

The prisoners taken in the battle informed them about Emperor Heraclius's final effort to take back Syria. They said that an army possibly two hundred thousand (200,000) strong would soon emerge to recapture the province. Khalid stopped here on June 636. This huge army set out for their destination. As soon as Abu Ubaida heard the news, he gathered all his officers to plan their next move. Khalid suggested that they should summon all of their forces present in the province of Syria (Syria, Jordan, Palestine) and to make a powerful joint force and then move towards the plain of Yarmouk for battle.

Abu Ubaida ordered all the Muslim commanders to withdraw from all the conquered areas, return the tributes that they previously gathered, and move towards Yarmuk.[26] Heraclius's army also moved towards Yarmuk. The Muslim armies reached it in July 636. A week or two later, around mid July, the Byzantine army arrived.[27] Khalid's mobile guard defeated Christian Arab auxiliaries of the Roman army in a skirmish.

Nothing happened until the third week of August in which the Battle of Yarmouk was fought. The battle lasted 6 days during which Abu Ubaida transferred the command of the entire army to Khalid. The five times larger Byzantine army was defeated in October 636 CE. Abu Ubaida held a meeting with his high command officers, including Khalid to decide on future conquests. They decided to conquer Jerusalem. The siege of Jerusalem lasted four months after which the city agreed to surrender, but only to Caliph Umar Ibn Al Khattab in person. Amr ibn Al As suggested that Khalid should be sent as Caliph, because of his very strong resemblance of Caliph Umar.

Khalid was recognized and eventually, Caliph Umar ibn Al Khattab came and Jerusalem surrendered on April 637 CE. Abu Ubaida sent the commanders Amr bin al-As, Yazid bin Abu Sufyan, and Sharjeel bin Hassana back to their areas to reconquer them. Most of the areas submitted without a fight. Abu Ubaida himself along with Khalid, moved to northern Syria once again to conquer it with a 17,000 man army. Khalid along with his cavalry was sent to Hazir and Abu Ubaidah moved to the city of Qasreen.

Khalid defeated a strong Byzantine army at the Battle of Hazir and reached Qasreen before Abu Ubaidah. The city surrendered to Khalid. Soon, Abu Ubaidah arrived in June 637. Abu Ubaidah then moved against Aleppo. As usual Khalid was commanding the cavalry. After the Battle of Aleppo the city finally agreed to surrender in October 637.

Occupation of AnatoliaEdit

Abu Ubaida and Khalid ibn Walid, after conquering all of northern Syria, moved north towards Anatolia conquering the fort of Azaz to clear the flank and rear from Byzantine troops. On their way to Antioch, a Roman army blocked them near a river on which there was an iron bridge. Because of this, the following battle is known as the Battle of the Iron Bridge. The Muslim army defeated the Byzantines and Antioch surrendered on 30 October 637 CE. Later during the year, Abu Ubaida sent Khalid and another general named Ayaz bin Ghanam at the head of two separate armies against the western part of Jazira, most of which was conquered without strong resistance, including parts of Anatolia, Edessa and the area up to the Ararat plain. Other columns were sent to Anatolia as far west as the Taurus Mountains, the important city of Marash and Malatya which were all conquered by Khalid in the autumn of 638 CE. During Uthman's reign, the Byzantines recaptured many forts in the region and on Uthman's orders, a series of campaigns were launched to regain control of them. In 647 Muawiyah, the governor of Syria sent an expedition against Anatolia. They invaded Cappadocia and sacked Caesarea Mazaca. In 648 the Rashidun army raided Phrygia. A major offensive into Cilicia and Isauria in 650–651 forced the Byzantine Emperor Constans II to enter into negotiations with Uthman's governor of Syria, Muawiyah. The truce that followed allowed a short respite, and made it possible for Constans II to hold on to the western portions of Armenia. In 654–655 on the orders of Uthman, an expedition was preparing to attack the Byzantine capital Constantinople but this plan was not carried out due to the civil war that broke out in 656.

The Taurus Mountains in Turkey marked the western frontiers of the Rashidun Caliphate in Anatolia during Caliph Uthman's reign.

Conquest of EgyptEdit

At the commencement of the Muslim conquest of Egypt, Egypt was part of the Byzantine Empire with its capital in Constantinople. However, it had been occupied just a decade before by the Sassanid Empire under Khosrau II (616 to 629 CE). The power of the Byzantine Empire was shattered during the Muslim conquest of Syria, and therefore the conquest of Egypt was much easier. In 639 some 4000 Rashidun troops led by Amr ibn al-As were sent by Umar to conquer the land of the ancient pharaohs. The Rashidun army crossed into Egypt from Palestine in December 639 and advanced rapidly into the Nile Delta. The imperial garrisons retreated into the walled towns, where they successfully held out for a year or more. But the Muslims sent for reinforcements and the invading army, joined by another 12,000 men in 640, defeated a Byzantine army at the Battle of Heliopolis. Amr next proceeded in the direction of Alexandria, which was surrendered to him by a treaty signed on 8 November 641. The Thebaid seems to have surrendered with scarcely any opposition.

The ease with which this valuable province was wrenched from the Byzantine Empire appears to have been due to the treachery of the governor of Egypt, Cyrus,[28] Melchite (i.e., Byzantine/Chalcedonian Orthodox, not Coptic) Patriarch of Alexandria, and the incompetence of the generals of the Byzantine forces, as well as due to the loss of most of the Byzantine troops in Syria against the Rashidun army. Cyrus had persecuted the local Coptic Christians. He is one of the authors of monothelism, a seventh-century heresy, and some supposed him to have been a secret convert to Islam.

During the reign of Caliph Uthman an attempt was made in the year 645 to regain Alexandria for the Byzantine empire, but it was retaken by Amr in 646. In 654 an invasion fleet sent by Constans II was repulsed. From that time no serious effort was made by the Byzantines to regain possession of the country.

The Muslims were assisted by some Copts, who found the Muslims more tolerant than the Byzantines, and of these some turned to Islam. In return for a tribute of money and food for the troops of occupation, the Christian inhabitants of Egypt were excused from military service and left free in the observance of their religion and the administration of their affairs. Others sided with the Byzantines, hoping that they would provide a defense against the Arab invaders.[29] During the reign of Caliph Ali, Egypt was captured by rebel troops under the command of former Rashidun army general Amr ibn al-As, who killed Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr the governor of Egypt appointed by Ali.

Conquest of North AfricaEdit

After the withdrawal of the Byzantines from Egypt, the Exarchate of Africa had declared its independence under its exarch, Gregory the Patrician. The dominions of Gregory extended from the borders of Egypt to Morocco. Abdullah Ibn Sa'ad used to send raiding parties to the west. As a result of these raids the Muslims got considerable booty. The success of these raids made Abdullah Ibn Sa'ad feel that a regular campaign should be undertaken for the conquest of North Africa.

Uthman gave him permission after considering it in the Majlis al Shura. A force of 10,000 soldiers was sent as reinforcement. The Rashidun army assembled in Barqa in Cyrenaica, and from there they marched west to capture Tripoli, after Tripoli the army marched to Sufetula, the capital of King Gregory. He was defeated and killed in the battle due to superb tactics used by Abdullah ibn Zubayr. After the Battle of Sufetula the people of North Africa sued for peace. They agreed to pay an annual tribute. Instead of annexing North Africa, the Muslims preferred to make North Africa a vassal state. When the stipulated amount of the tribute was paid, the Muslim forces withdrew to Barqa. Following the First Fitna, the first Islamic civil war, Muslim forces withdraw from north Africa to Egypt. The Ummayad Caliphate, re-invaded north Africa in 664.

Campaign against Nubia (Sudan)Edit

A campaign was undertaken against Nubia during the Caliphate of Umar in 642, but failed after the Makurians took victory at the First Battle of Dongola. The army was pulled out of Nubia without any success. Ten years later, Uthman’s governor of Egypt, Abdullah ibn Saad, sent another army to Nubia. This army penetrated deeper into Nubia and laid siege to the Nubian capital of Dongola. The Muslims damaged the cathedral in the center of the city, but the battle also went in favor of Makuria. As the Muslims were not able to overpower Makuria, they negotiated a peace with their king Qaladurut. According to the treaty that was signed, each side agreed not to make any aggressive moves against the other. Each side agreed to afford free passage to the other party through its territories. Nubia agreed to provide 360 slaves to Egypt every year, while Egypt agreed to supply grain, horses and textiles to Nubia according to demand.

Conquest of the islands of the Mediterranean SeaEdit

During Umar's reign, the governor of Syria, Muawiyah I, sent a request to build a naval force to invade the islands of the Mediterranean Sea but Umar rejected the proposal because of the risk of death of soldiers at sea. During his reign Uthman gave Muawiyah permission to build a navy after concerning the matter. In 650 CE the Arabs made the first attack on the island of Cyprus under the leadership of Muawiya. They conquered the capital, Salamis - Constantia, after a brief siege, but drafted a treaty with the local rulers. In the course of this expedition a relative of Muhammad, Umm-Haram fell from her mule near the Salt Lake at Larnaca and was killed. She was buried in that same spot which became a holy site for both many local Muslims and Christians and, much later in 1816, the Hala Sultan Tekke was built there by the Ottomans. After apprehending a breach of the treaty, the Arabs re-invaded the island in 654 CE with five hundred ships. This time, however, a garrison of 12,000 men was left in Cyprus, bringing the island under Muslim influence.[30] After leaving Cyprus the Muslim fleet headed towards the island of Crete and then Rhodes and conquered them without much resistance. In 652-654, the Muslims launched a naval campaign against Sicily and they succeeded in capturing a large part of the island. Soon after this Uthman was murdered, and no further expansion efforts were made, and the Muslims accordingly retreated from Sicily. In 655 Byzantine Emperor Constans II led a fleet in person to attack the Muslims at Phoinike (off Lycia) but it was defeated: 500 Byzantine ships were destroyed in the battle, and the emperor himself narrowly avoided death.

First Muslim invasion of the Iberian peninsulaEdit

In Islamic history the conquest of Spain was undertaken by forces led by Tariq ibn Ziyad and Musa ibn Nusair in 711–718 C.E, in the time of the Umayyad Caliph Walid ibn Abd al-Malik. According to Muslim historian Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari, Spain was first invaded by Muslims some sixty years earlier during the caliphate of Uthman in 653[citation needed]. Other prominent Muslim historians like Ibn Kathir have repeated Al-Tabari's assertion.[citation needed]

According to al-Tabari's account, when North Africa had been conquered by Abdullah Ibn Sa'ad, two of his generals, Abdullah ibn Nafiah ibn Husain, and Abdullah ibn Nafi' ibn Abdul Qais, were commissioned to invade coastal areas of Spain by sea.[citation needed]

No details of the campaigns in Spain during the caliphate of Uthman are given by al-Tabari. The account is merely to the effect that an Arab force, aided by a Berber force, landed in Spain and took possession of some coastal areas.[citation needed] The account is vague about what happened and where and whether or not it involved a prolonged local occupation or was merely a short lived military operation. As these regions were populated, an occupation would not have gone unnoticed by the inhabitants. Nor do later Muslim accounts mention any pre-Ummayad Muslim settlements or forts in the Iberian Peninsula. Al-Tabari's assertion remains unconfirmed by independent sources.

Treatment of conquered peoplesEdit

The non-Muslim monotheist inhabitants - Jews, Zoroastrians, and Christians of the conquered lands were called dhimmis (the protected people). Those who accepted Islam were treated in a similar manner as other Muslims, and were given equivalent rights in legal matters. Non-Muslims were given legal rights according to their faiths' law except where it conflicted with Islamic law.

In some senses, Islamic law made dhimmis second-class citizens. For instance, a Muslim woman could not marry a Non-Muslim man, and the son of a Muslim man and a dhimmi woman was always considered a Muslim, with no choice left to the individual. Dhimmis were allowed to "practice their religion, and to enjoy a measure of communal autonomy" and were guaranteed their personal safety and security of property, but only in return for paying tax and acknowledging Muslim rule.[31] Dhimmis were also subject to pay jizya (Muslims were expected to pay zakāt and kharaj[32]). Disabled dhimmis did not have to pay jizya and, were even given a stipend by the state.

The Rashidun caliphs had placed special emphasis on relative fair and just treatment of the dhimmis. They were also provided 'protection' by the Islamic empire and were not expected to fight; rather the Muslims were entrusted to defend them. Sometimes, in particular when there were not enough qualified Muslims, dhimmis were given important positions in the government.

Political administrationEdit

The basic administrative system of the Dar al-Islamiyyah (The House of Islam) was laid down in the days of the Prophet. Caliph Abu Bakr stated in his sermon when he was elected: "If I order any thing that would go against the order of Allah and his Messenger; then do not obey me". This is considered to be the foundation stone of the Caliphate. Caliph Umar has been reported to have said: "O Muslims, straighten me with your hands when I go wrong", and at that instance a Muslim man stood up and said "O Amir al-Mu'minin (Leader of the Believers) if you are not straightened by our hands we will use our sword to straighten you!". Hearing this Caliph Umar said "Alhamdulillah (Praise be to Allah) I have such followers."[citation needed]

In the administrative field Umar was the most brilliant among the Rashidun caliphs, and it was due to his exemplary administrative qualities that most of the administrative structures of the empire were established.[citation needed]

Under Abu Bakr the empire was not clearly divided into provinces, though it had many administrative districts.

Under Umar the Empire was divided into a number of provinces which were as follows:

- Arabia was divided into two provinces, Mecca and Medina;

- Iraq was divided into two provinces, Basra and Kufa;

- the province of Jazira was created in the upper reaches of the Tigris and the Euphrates;

- Syria was a province;

- Palestine was divided in two provinces: Aylya and Ramlah;

- Egypt was divided into two provinces: Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt;

- Persia was divided into three provinces: Khorasan, Azarbaijan, and Fars.

In his testament Umar had instructed his successor not to make any change in the administrative set up for one year after his death. Thus for one year Uthman maintained the pattern of political administration as it stood under Umar, however later he made some amendments. Uthman made Egypt one province and created a new province comprising North Africa. Syria, previously divided into two provinces, also become a single division.

During Uthman’s reign the empire was divided into twelve provinces. These were:

- Medina

- Mecca

- Yemen

- Kufa

- Basra

- Jazira

- Fars

- Azerbaijan

- Khorasan

- Syria

- Egypt

- North Africa

During Ali's reign, with the exception of Syria (which was under Muawiyah I's control) and Egypt (that he had lost during the latter years of his caliphate to the rebel troops of Amr ibn Al-A'as), the remaining ten provinces were under his control, which kept their administrative organizations as they were under Uthman.

The provinces were further divided into districts. Each of the 100 or more districts of the empire, along with the main cities, were administered by a governor (Wāli). Other officers at the provincial level were:

- Katib, the Chief Secretary.

- Katib-ud-Diwan, the Military Secretary.

- Sahib-ul-Kharaj, the Revenue Collector.

- Sahib-ul-Ahdath, the Police chief.

- Sahib-ul-Bait-ul-Mal, the Treasury Officer.

- Qadi, the Chief Judge.

In some districts there were separate military officers, though the governor was in most cases the commander-in-chief of the army quartered in the province.

The officers were appointed by the Caliph. Every appointment was made in writing. At the time of appointment an instrument of instructions was issued with a view to regulating the conduct of Governors. On assuming office, the Governor was required to assemble the people in the main mosque, and read the instrument of instructions before them.[33]

Umar's general instructions to his officers were:

| “ | "Remember, I have not appointed you as commanders and tyrants over the people. I have sent you as leaders instead, so that the people may follow your example. Give the Muslims their rights and do not beat them lest they become abused. Do not praise them unduly, lest they fall into the error of conceit. Do not keep your doors shut in their faces, lest the more powerful of them eat up the weaker ones. And do not behave as if you were superior to them, for that is tyranny over them." | ” |

During the reign of Abu Bakr the state was economically weak, while during Umar’s reign because of increase in revenues and other sources of income, the state was on its way to economic prosperity. Hence Umar felt it necessary that the officers be treated in a strict way as to prevent the possible greed for money that may lead them to corruption. During his reign, at the time of appointment, every officer was required to make the oath:

- That he would not ride a Turkic horse (which was a symbol of pride).

- That he would not wear fine clothes.

- That he would not eat sifted flour.

- That he would not keep a porter at his door.

- That he would always keep his door open to the public.

Caliph Umar himself followed the above postulates strictly. During the reign of Uthman the state become more economically prosperous than ever before; the allowance of the citizens was increased by 25% and the economical condition of the ordinary person was more stable, which lead Caliph Uthman to revoke the 2nd and 3rd postulates of the oath. At the time of appointment a complete inventory of all the possessions of the person concerned was prepared and kept in record. If there was an unusual increase in the possessions of the office holder, he was immediately called to account, and the unlawful property was confiscated by the State. The principal officers were required to come to Mecca on the occasion of the hajj, during which people were free to present any complaint against them. In order to minimize the chances of corruption, Umar made it a point to pay high salaries to the staff. Provincial governors received as much as five to seven thousand dirhams annually besides their share of the spoils of war (if they were also the commander-in-chief of the army of their sector).

Judicial administrationEdit

As most of the administrative structure of the Rashidun Empire was set up by Umar, the judicial administration was also established by him and the other Caliphs followed the same system without any type of basic amendment in it. In order to provide adequate and speedy justice for the people, an effective system of judicial administration was set up, hereunder justice was administered according to the principles of Islam.

Qadis (Judges) were appointed at all administrative levels for the administration of justice. The Qadis were chosen for their integrity and learning in Islamic law. High salaries were fixed for the Qadis so that there was no temptation to bribery. Wealthy men and men of high social status were appointed as Qadis so that they might not have the temptation to take bribes, or be influenced by the social position of any body. The Qadis were not allowed to engage in trade. Judges were appointed in sufficient number, and there was no district which did not have a Qadi.

Electing or appointing a CaliphEdit

Fred Donner, in his book The Early Islamic Conquests (1981), argues that the standard Arabian practice during the early Caliphates was for the prominent men of a kinship group, or tribe, to gather after a leader's death and elect a leader from amongst themselves, although there was no specified procedure for this shura, or consultative assembly. Candidates were usually from the same lineage as the deceased leader, but they were not necessarily his sons. Capable men who would lead well were preferred over an ineffectual direct heir, as there was no basis in the majority Sunni view that the head of state or governor should be chosen based on lineage alone.

This argument is advanced by Sunni Muslims that Muhammad's companion Abu Bakr was elected by the community, and this was the proper procedure. They further argue that a caliph is ideally chosen by election or community consensus. The caliphate became a hereditary office or the prize of the strongest general after the Rashidun caliphate. However, Sunni Muslims believe this was after the 'rightly guided' caliphate ended (Rashidun caliphate).

Abu Bakr Al-Baqillani has said that the leader of the Muslims simply should be from the majority. Abu Hanifa an-Nu‘man also wrote that the leader must come from the majority.[34]

Sunni beliefEdit

Following the death of Muhammad, a meeting took place at Saqifah. At that meeting, Abu Bakr was elected caliph by the Muslim community. Sunni Muslims developed the belief that the caliph is a temporal political ruler, appointed to rule within the bounds of Islamic law (The rules of life set by God in the quran). The job of adjudicating orthodoxy and Islamic law was left to Islamic lawyers, judiciary, or specialists individually termed as Mujtahids and collectively named the Ulema. The first four caliphs are called the Rashidun, meaning the Rightly Guided Caliphs, because they are believed to have followed the Qur'an and the sunnah (example) of Muhammad in all things.

Majlis al-Shura: ParliamentEdit

Traditional Sunni Islamic lawyers agree that shura, loosely translated as “consultation of the people”, is a function of the caliphate. The Majlis al-Shura advise the caliph. The importance of this is premised by the following verses of the Qur'an:

"...those who answer the call of their Lord and establish the prayer, and who conduct their affairs by Shura. [are loved by God]"[42:38]

"...consult them (the people) in their affairs. Then when you have taken a decision (from them), put your trust in Allah"[3:159]

The majlis is also the means to elect a new caliph. Al-Mawardi has written that members of the majlis should satisfy three conditions: they must be just, they must have enough knowledge to distinguish a good caliph from a bad one, and must have sufficient wisdom and judgment to select the best caliph. Al-Mawardi also said in emergencies when there is no caliphate and no majlis, the people themselves should create a majlis, select a list of candidates for caliph, then the majlis should select from the list of candidates.[34]

Some modern interpretations of the role of the Majlis al-Shura include those by Islamist author Sayyid Qutb and by Taqiuddin al-Nabhani, the founder of a transnational political movement devoted to the revival of the Caliphate. In an analysis of the shura chapter of the Qur'an, Qutb argued Islam requires only that the ruler consult with at least some of the ruled (usually the elite), within the general context of God-made laws that the ruler must execute. Taqiuddin al-Nabhani, writes that Shura is important and part of "the ruling structure" of the Islamic caliphate, "but not one of its pillars," and may be neglected without the Caliphate's rule becoming unislamic. Non-Muslims may serve in the majlis, though they may not vote or serve as an official.

Accountability of rulersEdit

Sunni Islamic lawyers have commented on when it is permissible to disobey, impeach or remove rulers in the Caliphate. This is usually when the rulers are not meeting public responsibilities obliged upon them under Islam.

Al-Mawardi said that if the rulers meet their Islamic responsibilities to the public, the people must obey their laws, but if they become either unjust or severely ineffective then the Caliph or ruler must be impeached via the Majlis al-Shura. Similarly Al-Baghdadi[clarification needed] believed that if the rulers do not uphold justice, the ummah via the majlis should give warning to them, and if unheeded then the Caliph can be impeached. Al-Juwayni argued that Islam is the goal of the ummah, so any ruler that deviates from this goal must be impeached. Al-Ghazali believed that oppression by a caliph is enough for impeachment. Rather than just relying on impeachment, Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani obliged rebellion upon the people if the caliph began to act with no regard for Islamic law. Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani said that to ignore such a situation is haraam, and those who cannot revolt inside the caliphate should launch a struggle from outside. Al-Asqalani used two ayahs from the Qur'an to justify this:

"...And they (the sinners on qiyama) will say, 'Our Lord! We obeyed our leaders and our chiefs, and they misled us from the right path. Our Lord! Give them (the leaders) double the punishment you give us and curse them with a very great curse'..."[33:67–68]

Islamic lawyers commented that when the rulers refuse to step down via successful impeachment through the Majlis, becoming dictators through the support of a corrupt army, if the majority agree they have the option to launch a revolution against them. Many noted that this option is only exercised after factoring in the potential cost of life.[34]

Rule of lawEdit

The following hadith establishes the principle of rule of law in relation to nepotism and accountability[35]

Narrated ‘Aisha: The people of Quraish worried about the lady from Bani Makhzum who had committed theft. They asked, "Who will intercede for her with Allah's Apostle?" Some said, "No one dare to do so except Usama bin Zaid the beloved one to Allah's Apostle." When Usama spoke about that to Allah's Apostle Allah's Apostle said: "Do you try to intercede for somebody in a case connected with Allah’s Prescribed Punishments?" Then he got up and delivered a sermon saying, "What destroyed the nations preceding you, was that if a noble amongst them stole, they would forgive him, and if a poor person amongst them stole, they would inflict Allah's Legal punishment on him. By Allah, if Fatima, the daughter of Muhammad (my daughter) stole, I would cut off her hand."

Various Islamic lawyers do however place multiple conditions, and stipulations e.g. the poor cannot be penalised for stealing out of poverty, before executing such a law, making it very difficult to reach such a stage. It is well known during a time of drought in the Rashidun caliphate period, capital punishments were suspended until the effects of the drought passed.

Islamic jurists later formulated the concept of the rule of law, the equal subjection of all classes to the ordinary law of the land, where no person is above the law and where officials and private citizens are under a duty to obey the same law. A Qadi (Islamic judge) was also not allowed to discriminate on the grounds of religion, gender, colour, kinship or prejudice. There were also a number of cases where caliphs had to appear before judges as they prepared to take their verdict.[36]

According to Noah Feldman, a law professor at Harvard University, the legal scholars and jurists who once upheld the rule of law were replaced by a law governed by the state due to the codification of Sharia by the Ottoman Empire in the early 19th century:[37]

EconomyEdit

During the Rashidun Caliphate there was an economic boom in the lives of the ordinary people due to the revolutionary economic policies developed by Umar and his successor Uthman. At first it was Umar who introduced these reforms on strong bases, his successor Uthman who himself was an intelligent businessman, further reformed them. During Uthman's reign the people of the empire enjoyed a prosperous life.

Bait-ul-MaalEdit

Bait-ul-Maal, (literally, The house of money) was the department that dealt with the revenues and all other economic matters of the state. In the time of Muhammad there was no permanent Bait-ul-Mal or public treasury. Whatever revenues or other amounts were received were distributed immediately. There were no salaries to be paid, and there was no state expenditure. Hence the need for the treasury at the public level was not felt.

Abu Bakr earmarked a house where all money was kept on receipt. As all money was distributed immediately the treasury generally remained locked up. At the time of the death of Abu Bakr there was only one dirham in the public treasury.

Establishment of Bait-ul-MaalEdit

In the time of Umar things changed. With the extension in conquests money came in larger quantities, Umar also allowed salaries to men fighting in the army. Abu Huraira who was the Governor of Bahrain sent a revenue of five hundred thousand dirhams. Umar summoned a meeting of his Consultative Assembly and sought the opinion of the Companions about the disposal of the money. Uthman ibn Affan advised that the amount should be kept for future needs. Walid bin Hisham suggested that like the Byzantines separate departments of treasury and accounts should be set up.

After consulting the Companions Umar decided to establish the central Treasury at Medina. Abdullah bin Arqam was appointed as the Treasury Officer. He was assisted by Abdur Rahman bin Awf and Muiqib. A separate Accounts Department was also set up and it was required to maintain record of all that was spent. Later provincial treasuries were set up in the provinces. After meeting the local expenditure the provincial treasuries were required to remit the surplus amount to the central treasury at Medina. According to Yaqubi the salaries and stipends charged to the central treasury amounted to over 30 million dirhams.

A separate building was constructed for the royal treasury by the name bait ul maal, which in large cities was guarded by as many as 400 guards.

In most of the historical accounts it states that among the Rashidun Caliphs Uthman ibn Affan was the first to strike coins; some accounts however state that Umar was the first to do so. When Persia was conquered three types of coins were current in the conquered territories, namely Baghli of eight dang; Tabari of four dang; and Maghribi of three dang. Umar (according to some accounts Uthman) made an innovation and struck an Islamic dirham of six dang.

Social welfare and pensions were introduced in early Islamic law as forms of zakāt (charity), one of the Five Pillars of Islam, since the time of the Rashidun caliph Umar in the 7th century. The taxes (including zakāt and jizya) collected in the treasury of an Islamic government were used to provide income for the needy, including the poor, elderly, orphans, widows, and the disabled. According to the Islamic jurist Al-Ghazali (Algazel, 1058–1111), the government was also expected to stockpile food supplies in every region in case a disaster or famine occurred. The Caliphate was thus one of the earliest welfare states.[38][39]

Economic resources of the StateEdit

The economic resources of the State were:

- Zakāt

- Ushr

- Jazya

- Fay

- Khums

- Kharaj

ZakatEdit

Zakāt (Arabic: زكاة) is the Islamic concept of luxury tax. It was taken from the Muslims in the amount of 2.5% of their dormant wealth (over a certain amount unused for a year) to give to the poor. Only persons whose annual wealth exceeded a minimum level (nisab) were collected from. The nisab does not include primary residence, primary transportation, moderate amount of woven jewelry, etc. Zakāt is one of the Five Pillars of Islam and it is obligation on all Muslims who qualify as wealthy enough.

JizyaEdit

Jizya or jizyah (Arabic: جزْية; Ottoman Turkish: cizye). It was a per capita tax imposed on able bodied non-Muslim men of military age since non-Muslims did not have to pay zakāt. The tax was not supposed to be levied on slaves, women, children, monks, the old, the sick,[40] hermits and the poor.[41] It is important to note that not only were some non-Muslims exempt (such as sick, old), they were also given stipends by the state when they were in need. [41]

FayEdit

Fay was the income from State land, whether an agricultural land or a meadow, or a land with any natural mineral reserves.

KhumsEdit

Ghanimah or Khums was the booty captured on the occasion of war with the enemy. Four-fifths of the booty was distributed among the soldiers taking part in the war while one-fifth was credited to the state fund.

KharajEdit

Kharaj was a tax on agricultural land.

Initially, after the first Muslim conquests in the 7th century, kharaj usually denoted a lump-sum duty levied upon the conquered provinces and collected by the officials of the former Byzantine and Sassanid empires, or, more broadly, any kind of tax levied by Muslim conquerors on their non-Muslim subjects, dhimmis. At that time, kharaj was synonymous with jizyah, which later emerged as a poll tax paid by dhimmis. Muslim landowners, on the other hand, paid only ushr, a religious tithe, which carried a much lower rate of taxation.[42]

UshrEdit

Ushr was a reciprocal 10% levy on agricultural land as well as merchandise imported from states that taxed the Muslims on their products. Umar was the first Muslim ruler to levy ushr.

When the Muslim traders went to foreign lands for the purposes of trade they had to pay a 10% tax to the foreign states. Ushr was levied on reciprocal basis on the goods of the traders of other countries who chose to trade in the Muslim dominions.

Umar issued instructions that ushr should be levied in such a way so as to avoid hardship, that it will not affect the trade activities in the Islamic empire. The tax was levied on merchandise meant for sale. Goods imported for consumption or personal use but not for sale were not taxed. The merchandise valued at 200 dirhams or less was not taxed. When the citizens of the State imported goods for the purposes of trade, they had to pay the customs duty or import tax at lower rates. In the case of the dhimmis the rate was 5% and in the case of the Muslims' 2.5%. In the case of the Muslims the rate was the same as that of zakāt. The levy was thus regarded as a part of zakāt and was not considered a separate tax.

AllowanceEdit

Beginning of the allowanceEdit

After the Battle of Yarmouk and Battle of al-Qadisiyyah the Muslims won heavy spoils. The coffers at Medina became full to the brim and the problem before Umar was what should be done with this money. Someone suggested that money should be kept in the treasury for the purposes of public expenditure only. This view was not acceptable to the general body of the Muslims. Consensus was reached on the point that whatever was received during a year should be distributed.

The next question that arose for consideration was what system should be adopted for distribution. One suggestion was that it should be distributed on an ad hoc basis and whatever was received should be equally distributed. Against this view it was felt that as the spoils were considerable, that would make the people very rich. It was therefore decided that instead of ad hoc division the amount of the allowance to the stipend should be determined beforehand and this allowance should be paid to the person concerned regardless of the amount of the spoils. This was agreed to.

About the fixation of the allowance there were two opinions. There were some who held that the amount of the allowance for all Muslims should be the same. Umar did not agree with this view. He held that the allowance should be graded according to one's merit with reference to Islam.

Then the question arose as to what basis should be used for placing some above others. Suggested that a start should be made with the Caliph and he should get the highest allowance. Umar rejected the proposal and decided to start with the clan of Muhammad.

Umar set up a committee to compile a list of persons in nearness to Muhammad. The committee produced the list clan-wise. Bani Hashim appeared as the first clan. Then the clan of Abu Bakr, and in third place the clan of Umar. Umar accepted the first two placements but delegated his clan lower down on the scale with reference to nearness in relationship to Muhammad.

In the final scale of allowance that was approved by Umar the main provisions were:[citation needed]

- The widows of Muhammad received 12,000 dirhams each;

- `Abbas ibn `Abd al-Muttalib, the uncle of Muhammad received an annual allowance of 7000 dirhams;

- The grandsons of the Muhammad, Hasan ibn Ali and Hussain ibn Ali got 5000 dirhams each;

- The veterans of the Battle of Badr got an allowance of 6000 dirhams each;

- Those who had become Muslims by the time of the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah got 4000 dirhams each;

- Those who became Muslims at the time of the Conquest of Mecca got 3000 dirhams each;

- The veterans of the Apostasy wars got 3000 dirhams each.

- The veterans of the Battle of Yarmouk and the Battle of al-Qadisiyyah got 2000 dirhams each.

In this award Umar's son Abdullah ibn Umar got an allowance of 3000 dirhams. On the other hand, Usama ibn Zaid got 4000.

The ordinary Muslim citizens got allowances of between 2000 and 2500. The regular annual allowance was given only to the urban population, because they formed the backbone of the state's economic resources . The Bedouin living in the desert, cut off from the states affairs making no contributions in the developments were often given stipends. On assuming office, Caliph Uthman ibn Affan increased these stipends by 25%.[citation needed]

EvaluationEdit

That was an economic measure which contributed to the prosperity of the people at lot. The citizens of the Islamic empire became increasingly prosperous as trade activities increased. In turn, they contributed to the department of bait al maal and more and more revenues were collected.

Welfare worksEdit

The mosques were not mere places for offering prayers; these were community centers as well where the faithful gathered to discuss problems of social and cultural importance. During the caliphate of Umar as many as four thousand mosques were constructed extending from Persia in the east to Egypt in the west. The Masjid-e-Nabawi and al-Masjid al-Haram were enlarged first during the reign of Umar and then during the reign of Uthman ibn Affan who not only extended them to many thousand square meters but also beautified them on a large scale.

During the caliphate of Umar many new cities were founded. These included Kufa, Basra, and Fustat. These cities were laid in according with the principles of town planning. All streets in these cities led to the Friday mosque which was sited in the center of the city. Markets were established at convenient points, which were under the control of market officers who was supposed to check the affairs of market and quality of goods. The cities were divided into quarters, and each quarter was reserved for particular tribes. During the reign of Caliph Umar, there were restrictions on the building of palatial buildings by the rich and elites, this was symbolic of the egalitarian society of Islam, where all were equal, although the restrictions were later revoked by Caliph Uthman because of the financial prosperity of ordinary men, and the construction of double story building was permitted. As a result, many palatial buildings were constructed throughout the empire with Uthman himself building a huge palace for in Medina which was famous and, named Al-Zawar; he constructed it from his personal resources.

Many buildings were built for administrative purposes. In the quarters called Dar-ul-Amarat government offices and houses for the residence of officers were provided. Buildings known as Diwans were constructed for the keeping of official records. Buildings known as Bait-ul-Mal were constructed to house royal treasuries. For the lodging of persons suffering sentences as punishment, Jails were constructed for the first time in Muslim history. In important cities Guest Houses were constructed to serve as rest houses for traders and merchants coming from far away places. Roads and bridges were constructed for public use. On the road from Medina to Mecca, shelters, wells, and meal houses were constructed at every stage for the ease of the people who came for hajj.

Military cantonments were constructed at strategic points. Special stables were provided for cavalry. These stables could accommodate as many as 4,000 horses. Special pasture grounds were provided and maintained for Bait-ul-Mal animals. Canals were dug to irrigate fields as well as provide drinking water for the people. Abu Musa canal (after the name of governor of Basra Abu-Musa al-Asha'ari ) was a nine-mile (14 km) long canal which brought water from the Tigris to Basra. Another canal known as Maqal canal was also dug from the Tigris. A canal known as the Amir al-Mu'minin canal' (after the title Amir al-Mu'minin that was ordered by Caliph Umar) was dug to join the Nile to the Red Sea. During the famine of 639 food grains were brought from Egypt to Arabia through this canal from the sea which saved the lives of millions of inhabitants of Arabia. Sa`d ibn Abi Waqqas canal (After the name of governor of Kufa Sa`d ibn Abi Waqqas) dug from the Euphrates brought water to Anbar. 'Amr ibn al-'As the governor of Egypt, during the reign of Caliph Umar, even proposed the digging of a canal to join the Mediterranean to the Red Sea. This proposal, however, did not materialize due to unknown reasons, and it was 1200 years later that such a canal was dug, today's Suez Canal. Shuaibia was the port for Mecca. but it was inconvenient, so Caliph Uthman selected Jeddah as the site of the new seaport, and a new port was built there. Uthman also reformed the cities police departments.

MilitaryEdit

The Rashidun army was the primary military body of the Islamic armed forces of the 7th century, serving alongside the Rashidun navy. The Rashidun army maintained a very high level of discipline, strategic prowess and organization, along with motivation and self initiative of the officer corps. For much of its history this army was one of the most powerful and effective military forces in all of the region. At the height of the Rashidun Caliphate the maximum size of the army was around 100,000 troops.[43]

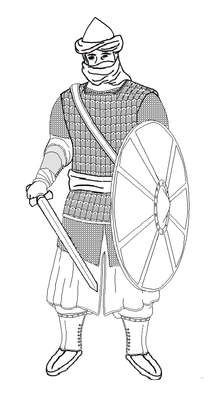

The Rashidun army was divided into the two basic categories, infantry and light cavalry. Reconstructing the military equipment of early Muslim armies is problematic. Compared with Roman armies or later medieval Muslim armies, the range of visual representation is very small, often imprecise and difficult to date. Physically very little material evidence has survived and again, much of it is difficult to date.[44] The soldiers used to wear iron and bronze segmented helmets that came from Iraq and were of Central Asian type.[45]

The standard form of protective body armor was chainmail. There are also references to the practice of wearing two coats of mail (dir’ayn), the one under the main one being shorter or even made of fabric or leather. Hauberks and large wooden or wickerwork shields were used as a protection in combat.[44] The soldiers were usually equipped with swords that were hung in a baldric. They also possessed spears and daggers.[46][page needed] Umar was the first Muslim ruler to organize the army as a State Department. This reform was introduced in 637. A beginning was made with the Quraish and the Ansar and the system was gradually extended to the whole of Arabia and to Muslims of conquered lands.

The basic strategy of early Muslim armies sent out to conquer foreign lands was to exploit every possible weakness of the enemy army in order to achieve victory. Their key strength was mobility. The cavalry had both horses and camels. The camels were used as both transport and food for long marches through the desert (Khalid bin Walid’s extraordinary march from the Persian border to Damascus utilized camels as both food and transport). The cavalry was the army’s main striking force and also served as a strategic mobile reserve. The common tactic used was to use the infantry and archers to engage and maintain contact with the enemy forces while the cavalry was held back till the enemy was fully engaged.

Once fully engaged the enemy reserves were absorbed by the infantry and archers, and the Muslim cavalry was used as pincers (like modern tank and mechanized divisions) to attack the enemy from the sides or to attack enemy base camps. The Rashidun army was quality-wise and strength-wise below standard compared with the Sassanid and Byzantine armies. Khalid ibn Walid was the first general of the Rashidun Caliphate to conquer foreign lands and to trigger the wholesale deposition of the two most powerful empires. During his campaign against the Sassanid Empire (Iraq 633 - 634) and the Byzantine Empire (Syria 634 - 638) Khalid developed brilliant tactics that he used effectively against both the Sassanid and Byzantine armies.

Abu Bakr's strategy was to give his generals their mission, the geographical area in which that mission would be carried out, and the resources that, could be made available for that purpose. He would then leave it to his generals to accomplish their missions in whatever manner they chose. On the other hand, Caliph Umar in the latter part of his Caliphate used to direct his generals as to where they would stay and when to move to the next target and who was to be commanding the left and right wing of the army in each particular battle. This made the phase of conquest comparatively slower but provided well-organized campaigns. Caliph Uthman used the same method as Abu Bakr: he would give missions to his generals and then leave it to them how they should accomplish it. Caliph Ali also followed the same method.

See alsoEdit

ReferencesEdit

|

|

This article has an unclear citation style. (September 2009) |

- ^ Azyumardi Azra (2006). Indonesia, Islam, and Democracy: Dynamics in a Global Context. Equinox Publishing (London). p. 9. ISBN 9789799988812.

- ^ C. T. R. Hewer; Allan Anderson (2006). Understanding Islam: The First Ten Steps (illustrated ed.). Hymns Ancient and Modern Ltd. p. 37. ISBN 9780334040323.

- ^ Anheier, Helmut K.; Juergensmeyer, Mark, eds. (9 Mar 2012). Encyclopedia of Global Studies. SAGE Publications. p. 151. ISBN 9781412994224.

- ^ Claire Alkouatli (2007). Islam (illustrated, annotated ed.). Marshall Cavendish. p. 44. ISBN 9780761421207.

- ^ Catharina Raudvere, Islam: An Introduction, (I.B.Tauris, 2015), 51-54.

- ^ Asma Afsaruddin (2008). The first Muslims: history and memory. Oneworld. p. 55.

- ^ Safia Amir (2000). Muslim Nationhood in India: Perceptions of Seven Eminent Thinkers. Kanishka Publishers, Distributors. p. 173. ISBN 9788173913358.

- ^ Heather N. Keaney (2013). Medieval Islamic Historiography: Remembering Rebellion. Sira: Companion- versus Caliph-Oriented History: Routledge. ISBN 9781134081066.

He also foretold that there would be a caliphate for thirty years (the length of the Rashidun Caliphate) that would be followed by kingship.

- ^ Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb; Johannes Hendrik Kramers; Bernard Lewis; Charles Pellat; Joseph Schacht (1970). "The Encyclopaedia of Islam". The Encyclopaedia of Islam (Brill). 3 (Parts 57-58): 1164.

- ^ Aqidah.Com (December 1, 2009). "The Khilaafah Lasted for 30 Years Then There Was Kingship Which Allaah Gives To Whomever He Pleases". Aqidah.Com. Aqidah.Com. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ^ http://www.taqawalife.com/2012/02/abu-ubaidah-bin-jarrah.html

- ^ https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/History/Caliphate.html

- ^ Balazuri: p. 113.

- ^ Tabari: Vol. 2, p. 467.

- ^ a b c d Gianluca Paolo Parolin, Citizenship in the Arab World: Kin, Religion and Nation-state, (Amsterdam University Press, 2009), 52.

- ^ Tabari: Vol. 2, p. 518

- ^ a b The Arab Conquest of Iran and its Aftermath, 'Abd Al-Husein Zarrinkub, The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4, ed. William Bayne Fisher, Richard Nelson Frye, (Cambridge University Press, 1999), 5-6.

- ^ Battle of Yarmouk River, Spencer Tucker, Battles That Changed History: An Encyclopedia of World Conflict, (ABC-CLIO, 2010), 92.

- ^ Khalid ibn Walid, Timothy May, Ground Warfare: An International Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, ed. Stanley Sandler, (ABC-CLIO, 2002), 458.

- ^ Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991), Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, p. 1892, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6

- ^ Egypt was conquered in 658 by Amr ibn al-As. Madelung (1997), pp. 267-269

- ^ A. I. Alkram. "Chapter 19: The Battle of Chains - Chapter 26: The Last Opposition". Khalid bin Al-Waleed: His Life and Campaigns. The Sword of Allah. p. 1.

- "Chapter 19: The Battle of Chains". p. 1. Archived from the original on Jan 26, 2002.

- "Chapter 20: The Battle of the River". p. 1. Archived from the original on 2002-03-06.

- "Chapter 21: The Hell of Walaja". p. 1. Archived from the original on 2002-03-06.

- "Chapter 22: The River of Blood". p. 1. Archived from the original on 2002-08-22.

- "Chapter 23: The Conquest of Hira". p. 1. Archived from the original on 2002-03-06.

- "Chapter 24: Anbar and Ain-ut-Tamr". p. 1. Archived from the original on 2002-03-06.

- "Chapter 25: Daumat-ul-Jandal Again". p. 1. Archived from the original on 2002-03-06.

- "Chapter 26: The Last Opposition". p. 1. Archived from the original on 2002-03-06.

- ^ D. Nicolle, Yarmuk 636 AD - The Muslim Conquest of Syria, p. 43: gives 9,000-10,000

- ^ a b A.I. Akram. "Chapter 31: The Unkind Cut". The Sword of Allah: Khalid bin Al-Waleed: His Life and Campaigns. p. 1. Archived from the original on Jan 5, 2003. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- ^ "Chapter 32: The Battle of Fahl". Khalid bin Al-Waleed: His Life and Campaigns. The Sword of Allah. p. 1. Archived from the original on Jan 10, 2003. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- ^ http://www.swordofallah.com/html/bookchapter34page1.htm[dead link]

- ^ http://www.swordofallah.com/html/bookchapter33page1.htm[dead link]

- ^ CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Cyrus of Alexandria Archived 13 February 2011 at WebCite

- ^ John, Bishop of Nikiu: Chronicle. London (1916). English Translation Archived 13 February 2011 at WebCite

- ^ Nadvi (2000), pg. 522

- ^ Lewis (1984), pp. 10, 20

- ^ Cl. Cahen in Encyclopedia of Islam - Jizya

- ^ The Cambridge History of Islam, ed. P.M. Holt, Ann K.S. Lambton, and Bernard Lewis, Cambridge 1970

- ^ a b c Gharm Allah Al-Ghamdy Archived 13 February 2011 at WebCite

- ^ Sahih Bukhari, Volume 4, Book 56, Number 681